Unlike most of the Muslim societies, the death in parts of Kashmir triggers a protracted commercial exercise that involves a set of professionals and a lot of costs. After meeting a couple of females who specialise in giving funeral baths to the dead while working in close coordination with the gravediggers, Saima Bhat tries to explain the elaborate business of the bones that has taken off with the death of traditional voluntarism in parts of the city

![]()

Art Work by a US-based artist, Zaffar Abbas

On the fourth day of mourning at Hazratbal, a discussion turned into verbal brawl soon after the family refused to give gold earrings and two bangles of their dead mother to the lady who prepared her mortal remains for interment. She gave her the funeral bath, the Ghasul.

“We already gave her Rs 2000, two suits and one pashmina shawl. But she is adamant that she has to take every gold ornament our mother was wearing at the time of her death,” says Arif, eldest son of the dead lady. “She doesn’t have an idea about what a golden ornament costs and how expensive a pashmina shawl usually is.”

Arif’s family actually belongs to Nawa Kadal area but a decade back they shifted to Hazratbal area. He said they could have managed to get some other lady, Ghusaal, a person who gives the ablutionary bath to the dead person before the burial, but the gravedigger insisted he works with this particular lady in the particular locality so there was no option. “A Gourkan, the gravedigger and a Ghusaal work with each other and there is a commercial relation,” Arif added.

The brawl ended in peace-making. Finally, the lady settled at Rs 7000 and the balance sum was to be paid on the Rasm-e-Chahrum, the fourth day of Arif’s mother.

Capital city’s areas are fairly distributed within the established Ghusaals’. Most of the Malkha area, the largest graveyard in Srinagar, comes under Laali ji’s domain. Though a daughter of adjacent Nowhatta, she is married outside the Old City.

In her early forties, Laali Ji, now a resident of Danderkha in Batamaloo, lives in a fully furnished newly constructed three storey house, the property she shares with her brother-in-law.

Having a distinct style of talking; she loves long sentences without missing her flow and skips normal pauses. She mostly prefixes Jigar before addressing a sentence towards any person she talks to. Having pierced her ears at four places in a row, with a gold earring in each, her naturally clean eyebrow line doesn’t hide the dark circles beneath her deep socket eyeballs. She is proud of her ‘profession’ and says it has come to her in Virasat, meaning she has inherited it. She doesn’t hesitate in saying that preparing dead for their eternal journey is her profession and everybody in her father’s family does it. She belongs to Hafiz family in Malkha, Nowhatta.

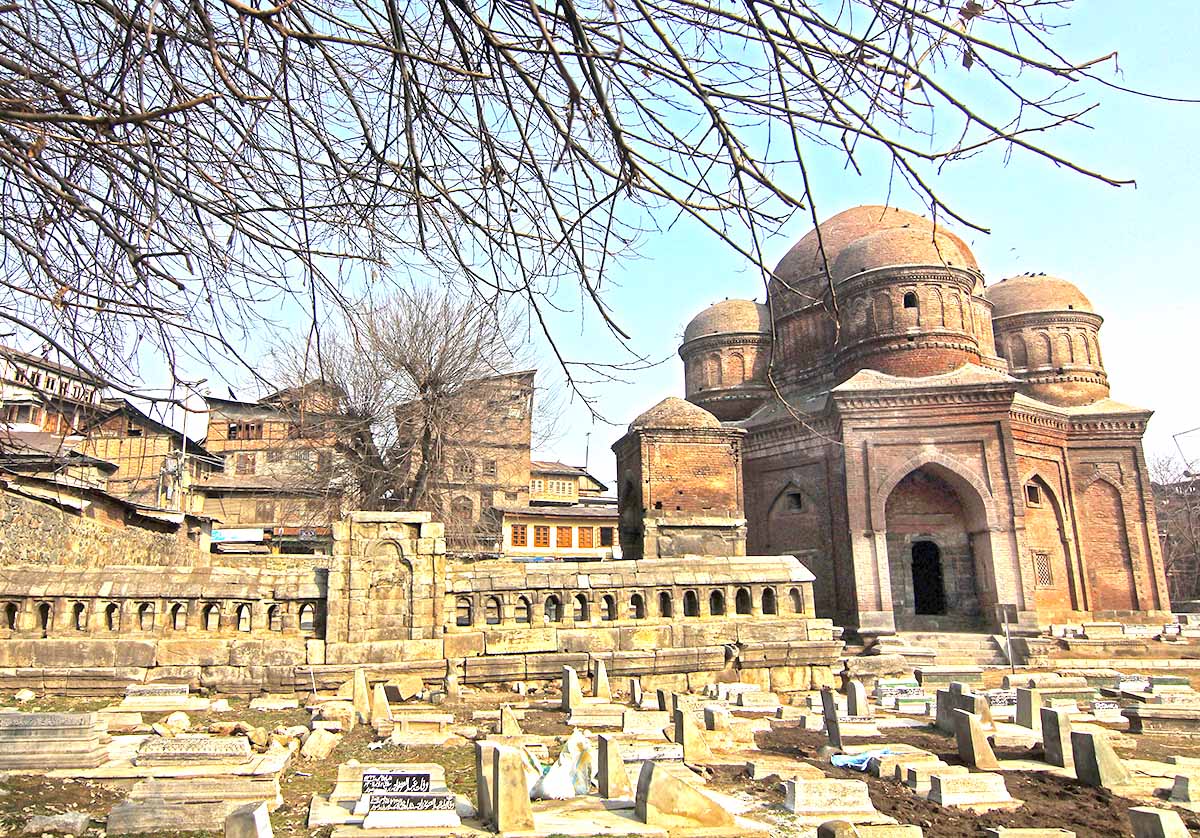

![]()

Aerial view of Malkha graveyard in Down Town, Srinagar. KL Image by Bilal Bahadur

“It is our ancestral occupation. My grandfather, grandmother and then my mother, father, brothers, uncles, cousins, everybody does the same work,” Laali Ji said. “If you are a doctor, Allah has given you this as your source of income, same ways this is ours.” The men in her family are gravediggers and the Ghusaals. She prepares the dead women for the burial and washes them for the final journey to the grave.

Laali Ji is illiterate but she says she has read the Quran and memorises all the verses that need to be recited for the dead at the time of their death. She was quick in claiming that if somebody opens the Quran in front of her she can read it from a distance. “When Grand Mufti’s mother passed away I was called for her Ghasul but before the actual job, they asked me, questioned me how I was going to do it,” Laali Ji remembers. “After they got convinced with my answers, they gave me a nod to go ahead. I have been approved by Kashmir’s Grand Mufti family so I can tell you with authority I am the only professional who knows her job well.”

But Laali Ji gets upsets when it comes to her predecessors and successors and immediately calls them ‘un-trained’, ‘unqualified’ for the job. She is in this undertaking profession from more than a decade now. It started the day her mother passed away in a road accident. It had become a crisis for her other family members in the profession as they had no female Ghusaal, locally called Srangarien. “I used to accompany my mother and I was aware how to do it but I had never done it,” Laali Ji recalls. “But after my mother’s death, I had to take over as my four siblings: two sisters and two brothers were still unmarried. Rest of us were married and settled so it was my responsibility to take over.”

Before getting into the profession, Laali Ji asked her husband, Firdous Ahmad Shah, a professional auto driver, if she can take over. To her surprise, she said he was supportive to get her the ‘noble mission’. But it was not an easy task for her. She had to undergo a six months training before taking over.

Laali Ji’s father was a poor man and could hardly earn two meals. She turns melancholic while recalling her childhood days when her father could not afford a second salwar kameez for his daughters. “I could study only up to the fifth primary because of the poverty and then I learnt the art of embroidery,” Lali Ji recalls her past. She was married in a Shudra family who neither had a good source of income nor any huge property. Her in-laws belonged to Sarai Bala area in Lal Chowk but later they shifted to Danderkha.

“I had to get my unmarried siblings to my husband’s house and over the years we married three of them,” she said, in appreciation of her in-laws. “My one brother is mentally unwell so we are not going to marry him. We have seriously worked like labourers for this extra responsibility.” Laali Ji and Shah have two children, a daughter who is studying in the eleventh standard and a son, a ninth grader.

In Muslim societies, giving Ghasul is a noble deed. It is one of the key rites in Muslim funerals. In most of the Muslim world, this is a voluntary exercise.

Gourkan and Ghusaal are Persian words, Gour meaning grave and Kan mean digger. With the advent of Islam in Kashmir, Islamic preachers got these Gourkans and Ghusaal along from central Asian countries.

“Those people taught locals about this job but in the old city, it was one particular class who learnt it,” Kashmir raconteur, Zareef Ahmad Zareef said. “But in rural areas, they did not keep it limited to one class only. At both places, these professionals used to work under a barter system.”

![]()

People carrying a body for funeral prayers. KL Image by Bilal Bahadur

In Kashmir, however, many people in urban spaces have suffered sort of a stigma attached to it, especially in the Old City. The gradual fading away of the voluntary spirit on this front has given birth to a formal profession and for the generations, it has survived as commerce. As it emerged a profession, the state could not avoid enlisting the Gorkan and the Gusaal as the social castes thus bestowing upon them certain concessions in recruitment and scholarships. As a result, an old city resident says, “These Gorkan’s and Ghusaal’s have shifted their profession. They are mostly doing white collar jobs now and for this work, they have hired labour to retain the social caste.” Laali Ji also says the people living in and around Malkha whose profession is majorly based with the dead, have to suffer when it comes to their marriage. “We are being called Malkhaish when I should be called Otan ji. They should call us with respect. Now instead of going out of the area, we prefer to marry between cousins so that our profession does not become a barrier in getting us good marriage prospects,” she said.

In Malkha, every clan has their allotted spaces. This peculiar fragmentation of city’s oldest and the biggest graveyard is known to the gravediggers like palms of their hands. When somebody passes away, the family comes to the graveyard and asks the concerned people to dig a grave. These families are aware if they seek the services of a gravedigger then they have to avail the entire basket of funeral services the particular Gorkan offers and it usually includes the Ghusaal.

“My area is vast because my father, brothers and cousins have only me as female support,” says Laali Ji. Her cousins get the address from the messenger of the family and she gets a call. Her husband accompanies her.

“My husband does not go for any work,” Laali Ji said. “He is full time with me because you never know when I will receive a call. I am hardly home. Sometimes it is midnight and sometimes during the day but my phone never stops ringing. People know my work and that is why I am in demand.” Since people inhabiting the old Srinagar city have started migrating to the uptown and other peripheral areas for better living in uncongested localities, Laali Ji says her area of operation has widened. Off late, she goes in the areas like Soura, Aali Kadal, Hyderpora, Baghat, Rajbagh, Bagh e Mehtab, Solina.

But as per Laali Ji the cost for Ghasul varies from family to family. If the areas fall under committees then it is the Mohalla committee that finalises the rate, which usually does not exceed Rs 3000. But, if the family approaches her directly or is not under committee then it involves sort of a bargain.

“See if they can spend lavishly on Wazwan on the fourth day of the mourning then why can’t they give us Rs 20,000 or more,” Laali Ji said. “Other than the money we are given jewellery the dead was wearing at the time of her death, some of her clothes as well and I accept everything with a Bismillah. Some of the ladies before dying tell their families that their earrings should be given to the lady who will prepare her for the last journey.” She says she is actually doing what the dead lady’s daughter, a mother or a close relative is supposed to do. “Why cannot they pay us well for the job they are supposed to do but do not do?” In case, the mourning families seek the return of the jewellery, she obliges, she claimed.

Transactions do not happen at the same time. Laali Ji said she meets the families on the fourth day of the mourning.

Laali Ji has many anecdotes to share. She remembers the accidental death of a mother whose leg had fallen off the body in the mishap. “Since I am not a doctor that I could have stitched it back but I tried to fix it with the bandages and when her husband saw it, he was impressed by my work and he gave me a cash reward,” she said.

The clothes she collects from the dead, she said, are stocked at her home. “Any needful comes and asks for clothes. I donate them,” she said. “People come to me because I have been doing it from years.” She says she is still in the profession because she has to earn for her two children and three minor children of her eldest brother, who has recently passed away.

There are counterpoints to her claims. “She collects these clothes and then they hire a vehicle and these clothes are sold out in open market,” one person, talking anonymously, said. He knows how the funeral undertaking operates in Kashmir. “She and her other co-professionals, however, retain the bedding of the dead along with the jewellery and the Pashmina shawls. It is sort of extortion.”

Many other female Ghusaals’ in downtown area demand above Rs 10,000 to whatever rate gets finalised in the bargain.

In 2007 when a colleague and friend of Zareef Ahmad Zareef passed away, he was witness to the ‘extortion’. “After burying my friend the gravedigger asked for Rs 15000 and everybody was shocked. Me and his brother-in-law, who was a senior officer in police refused to pay him that amount but my friend’s son handed over the money to him silently,” Zareef said. “It is an emotional state where nobody wants to argue that too when the dead is just buried.”

He claims to have witnessed scenes in which the relatives of a dead were interrupted while taken out the gold ornaments from a dead lady’s body. “You won’t believe how a Ghusaal started shouting, ye kya laash khaali (why is this body empty)…ye cha laash (is it really dead)…”

However, he insists the trend in vogue is a post- 1990 when the money flow started endlessly in Kashmir. Earlier, he said, these people were given a maximum of Rs 400.

Shaheena (name changed), 38, is also in the profession for the last five years. But it was after her husband heart ailment that she had to get in this profession. “My father’s family does not belong to this work but my in-laws do,” she said. “My husband was a gravedigger but some years back he developed heart ailment and started staying home.” The couple had two children and were living a single room house in Old City.

An illiterate Shaheena knew to spin the wheel but that did not fetch her much. One day she was asked by her father-in-law and husband to get in the profession so that she can earn respectably for her family. “It was on the body of my own daughter that I learnt giving Ghasul and it was my daughter who helped me in learning the Quranic verses that I need while preparing the dead,” she said.

After more than six years now Shaheena’s husband has recovered and changed his profession. He now sells different things on a cart and together they could save some money. Recently, they purchased a three storey house just opposite to her one-room home. This has helped the couple not to discontinue the studies of their children. She operates in areas of Nawa Kadal, Eidgah, Chattabal, Bemina.

But the commercial funeral undertaking is by and large restricted to the Old City. It has an elaborate system. It started with the funeral bath, the grave-digging, then the Pirs come for special prayers and the process continues until the Rasm-e-Chahrum is over. During the process of burial, the gravediggers seek unbaked bricks for which a number of shops operate near the Nowhatta police station, outside the Malkhah. On the fourth day, invariably, the deceased family invests in a grand feast. It follows the special prayers at the graveyard at a fixed time before which an epitaph is placed on the grave that is fixed with cement or the marble. The entire process is commercial.

During the mourning, the relatives come with eatables, most of which goes to waste. Though the families of the deceased are supposed to be fed by neighbours, the role has now been taken over by the Mohalla Committees that feed the families – only dinner – for three days.

The death is a huge business in most of the world. In certain non-pagan societies, the post-death rites are managed by huge companies, some of which are listed with the stock exchanges. But in most of the Muslim world, it is taking care of either by the society or by the state.

In Kashmir, this commercial phenomenon, however, does not exist outside Srinagar’s old city. People take it as a social service rather than a profession in areas surrounding the downtown.

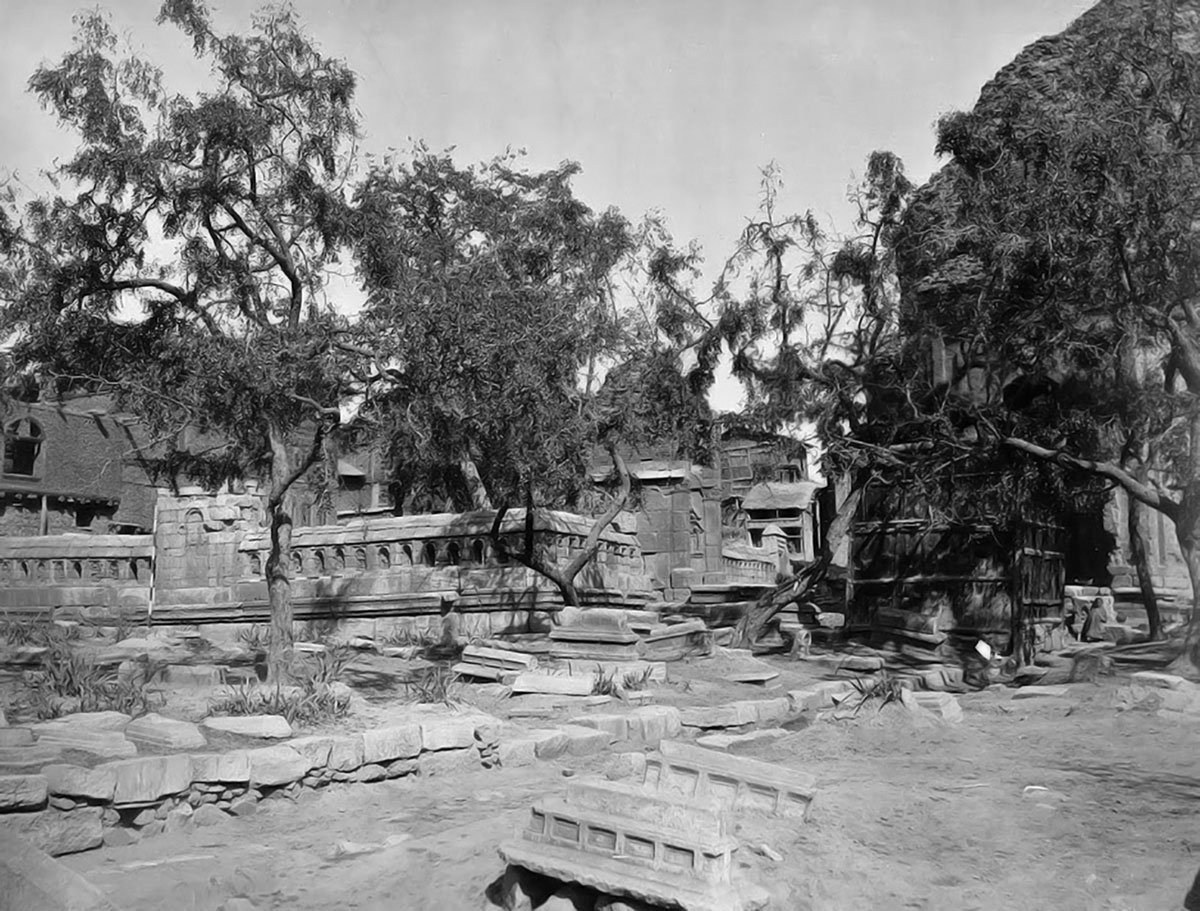

![]()

Graveyard in Srinagar. KL Image by Bilal Bahadur

Barely 2.5 km away from Lal Chowk, in Barzulla area, two septuagenarian women are known to prepare ladies for their eternal resting place. When Shakeela, a carcinoma breast patient succumbed to her disease in the first week of December, both the elderly Ghusaals’ were unwell. It was the dead lady’s immediate neighbour who went to inform them their services are needed.

“It is winter and usually old people don’t keep well. Then I was told that there was another lady who can help me but once I reached her home, she was accompanying her daughter-in-law in the hospital,” Abdul Majid said. “I was desperately exploring all the options and I came to know that a young girl, who was recently married in our area, knows this well.” When Shakeela’s neighbour, Majid, got the address he found a fully covered girl and asked her if she can come over to other Mohalla as a lady has died. She has learned it from a local Darsgah near her home.

By that time, Majid had informed a group of local boys about the demise in the neighbourhood and they had started digging a grave.

This all happened in just 15 minutes that the grave was ready and a lady was ready to give the funeral bath to the dead. “It was not only that girl who prepared the dead but her daughter and sister also helped in,” an eyewitness who was part of the funeral gathering said. “After the coffin was taken towards the graveyard, all of the Shakeela’s relatives and neighbour ladies were kissing the hands of that girl.”

In the peripheries of Srinagar City or the rural areas, neither the gravediggers are professionals nor the Ghusaals’ have a full-time job. They live a normal life without fearing any social stigma and do noble work as well.

Historian Mohammad Ashraf Wani links the phenomenon with pre-modern society. The Ghusaals and Gourkans were usually landless people and for their services, they were helped through a barter system. “After the advent of Islam, this profession became hereditary. But after modern commercialisation the system has changed,” Wani said. “In the City, they were limited people and things changed abruptly after the monetisation of the economy. And in rural areas, it was not limited to a particular class so there was not any problem.”

Wani believes the commercialisation of this work is fading away outside the old city with the people getting religiously conscious.

Islamic Scholar Mufti Tahira, who herself lives in the downtown area, says preparing a dead for her/his last journey is noble work. As per Islamic teachings, Mufti Tahira said it is the responsibility of the children to take care of their parents and if any of the parents dies it becomes the responsibility of their children to prepare them cleanly under pardah for the last journey. “We as children should not waste this opportunity of last Khidmat to our parents,” she insisted. She herself has faced an embarrassing situation when, at one mourning, she was requested to prepare a dead lady for the last journey. “They had already called in the professional Ghusaal and trust me she did not allow me to even touch the dead. I understand it is their source of income but I blame families for this wrong in the society.”

Tahira runs a school exclusively for females where she teaches Quran and other Islamic teachings. “I have made it mandatory for my girl students that they should know how to prepare dead for the burial and I counsel them how it is their responsibility to do it for their dear ones. I teach them on dummies how to do the Ghasul and then wear the Kafan (shroud) as per Shariah.”

When Tahira’s mother-in-law passed away in 2016, and her in-laws were going to call a Ghusaal, she interrupted them. She said she was going to do it herself and made her sisters-in-law also to help her. “It is our responsibility. The right of daughters is to do it for their mothers under Pardah. Who else can do Pardah for a mother other than a daughter?”

Caught between the profession, tradition and the faith, there are instances where female Ghusaals’ were arrested by police on the complaint filed by mourning families that they have stolen the jewellery of the dead. They were released after the recovery of the gold items.

“How can these ladies take the gold of dead when it becomes the property of her children,” Tahira said. “In our faith, there are strict rules for taking the share of orphans.”

Seeing the trend as counter-religious, anti-Sharia and unethical, Zareef said he visited the office of the Wakf Board thrice during recent years. “I have asked them that they should be recruiting professionals for Malkha and other bigger graveyards and fix an amount for their services. This is the only way to come out of this mess,” he said. “There were promises but nothing changed.”

Off late, as the Srinagar started expanding fast, another crisis has surfaced: the shortage of graveyards.

Haji Abdul Razak, a Sopore contractor, shifted to Srinagar after Kashmir engulfed in conflict. He lives in posh Baghat belt in the city uptown.

After more than two decades when he passed away in 2013, his mortal remains were driven to Sopore because he could not afford to buy a graveyard in the area he lived.

Saleem, his son, said they had contacted land dealers a couple of times but the rate of land was so high that they gave up the idea. “One can think of getting land for building his house in Srinagar but when it comes to graveyard same amount is needed for one marla of land for a graveyard,” Saleem said.

Zareef sees it as the worst thing happening in society. “Anything related to death has become a trade. The trade of dead has become worst of all trades in Kashmir.”

In order to manage this pressing requirement, a lucrative trade is flourishing in the city. As the people were hunting for the space to have exclusive graveyards, it was a soft speaking businessman who discovered an idea. He purchased vast patches of land falling under the power transmission lines within the city and its outskirts and converted them into graveyards.

“People do not like living under these lines for health reasons and this land was getting into disuse,” Mohammad Afzal Sheikh said. “I tried converting it into the graveyard and it clicked.” Now it is a roaring business. This idea has reduced the costs of the graveyard spaces to a large extent. “I believe, there is no space in Srinagar city and if it is it must be very costly,” Afzal said. “Invariably any fresh graveyard will not cost less than Rs 1.5 lakh a marla.”

Afzal has a fair understanding of this crisis. “If a non-resident dies in Srinagar, it is highly impossible that he would get a place for his eternal rest,” Afzal said. “One day, I was driving home that I saw a crowd near Buchpora. They were surrounding a cot on which was the corpse of a Bakerwal and he had no space to be buried. Then, I arranged from my resources some space in Rangil where he was laid to rest.”

The shortage of space and lack of a graveyard where a person, not having any rights over the cemetery, can be buried showed up humiliatingly at the peak of turmoil during the 1990s.

Since it was curfew and strikes, the moment was literally impossible, a small piece of land near the tertiary care maternity hospital Lala Ded hospital was converted into a graveyard for burying the infants who were dying in the hospital. “The hospital has not the facility of a corpse carrier. During Jagmohan’s tenure, the in-patients were hardly budging out. When the unprecedented curfews followed and their dead child started decomposing in the hospital complex, they decided to bury them in that piece of land infested with the wild grasses,” Masood Hussain reported in Kashmir Times on July 17, 1993. “Situation refused to regain its originality so the burials became a routine.”

![]()

A casket ready for sale.

The interesting feature of this “graveyard” was that it seems near vacant even after it had accommodated hundreds of dead juveniles since its existence on a temporary basis. Despite being put to constant with 28 infant burials a month, it never faced the space shortage, the report said. The reporter counted just two dozen “graves” among which “nine were wide open with recent blood stains shrouds though torn”. The report is one of the grim reminders of what Kashmir witnessed during the dark 1990s.

Though the hospital employees had collected some money to fill the stony boneyard, it was eventually abandoned after the situation improved.

But the crisis for people who lack rights over some sort of a resting space is getting inhuman. In Keran sector, Bore village ceases to exist. The residents were pushed out in the early 1990s and they live as migrants across Kashmir. When one resident died post-migration, he did not find any space and the family raised loans to purchase a few meters of land to bury him but still they could not manage it.

“It is absolute inhumanity,” Afzal said. “Why cannot Muslim Wakf Board start working for a graveyard where families, lacking resources to own such space, can bury the dead?”